Ordinary Differential Equations

General for of an ODE

where

The highest order of the derivatives is called the order of the ordinary differential equation.

Instead we may know a relationship between variable

Initial Value Problem

The general form is a differential equation

where

- By involving more than one unknown variable (not just

): Systems of differential equations - By solving second, third, or higher derivatives (not just

): Higher order differential equations

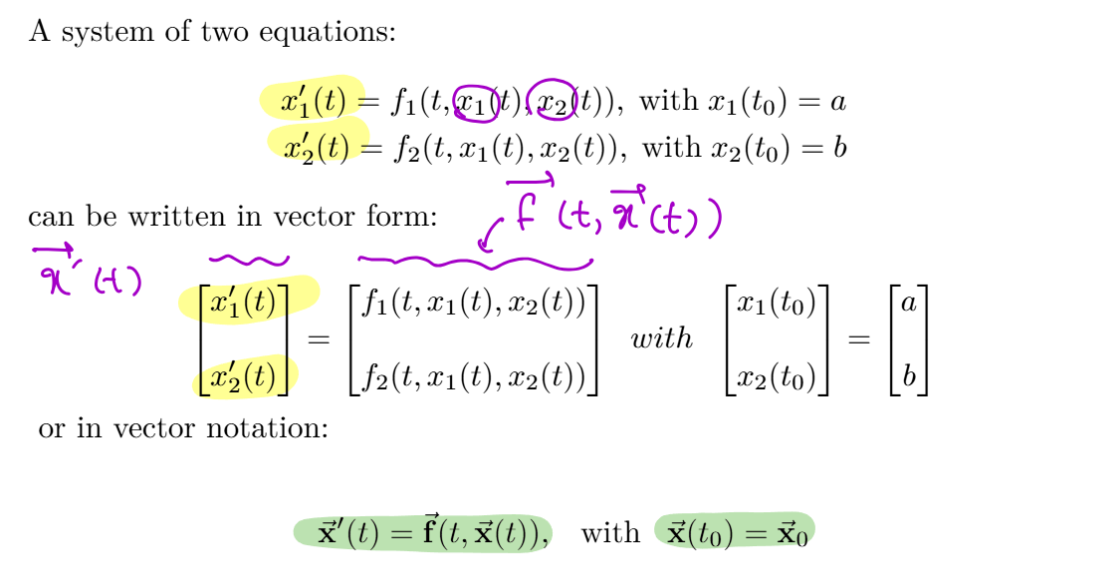

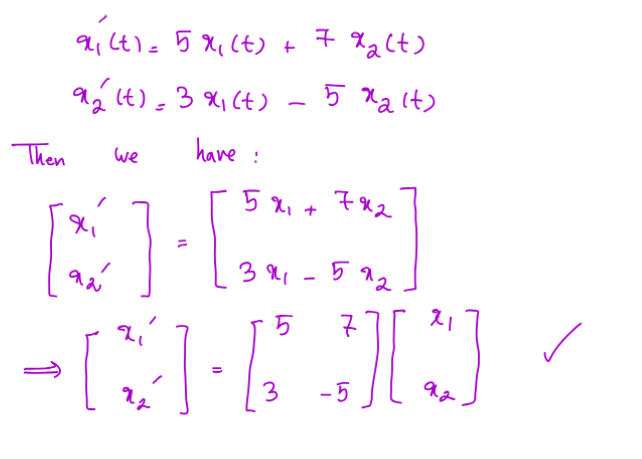

Systems of Differential Equations

Consider a model with multiple variables that interact:

- E.g.

and coordinates of a moving object.

This gives a system of differential equations, such as

- The matrix notation is specially helpful when

and are linear - The

can be decomposed as a constant matrix and a vector containing the functions

- The

Higher Order Differential Equations

To start, we consider 1st order ODEs, involving only first derivative

Numerical Schemes for ODEs

Numerical solution is a discrete set of time/value pairs,

should approximate the true value,

Time-Stepping

Given initial conditions, we repeatedly step sequentially forward to the next time instant, using the derivative info,

Set

- Compute

- Increment time,

- Advance,

- Repeat

Categorizing time-stepping methods

Single-step vs Multistep:

- Do we use information only from he current time or from previous timesteps too?

Explicit vs Implicit: - Is

given as an explicit function to evaluate, or do we need to solve an implicit equation?

Timestep size: - Do we use a constant timestep

, or allow it to vary?

Trade-offs

Explicit:

- Simpler and fast to compute per step

- Less stable - require smaller timesteps to avoid “blowing up”

Implicit: - Often more complex and expensive to solve per step

- More stable - can safely use larger timesteps

Time-Stepping as a Recurrence

Time-stepping applies a recurrence relation to approximate the function values at later and later times

- Given

, approximate . Given , approximate . etc.

Time-Stepping as a “Time Integration”

Time-stepping is also known as “time-integration”:

- We are integrating over time to approximate

from - Approximating area under the curve

Better time-stepping schemes correspond to better approximations of the integral

- Approximating area under the curve

Error of Time-Stepping

Absolute / global error at step

- We can’t measure error exactly without knowing

- We will rely on the Taylor series

Forward Euler

Explicit, single-step scheme

- Compute the current slope:

- Step in a straight line with that slope:

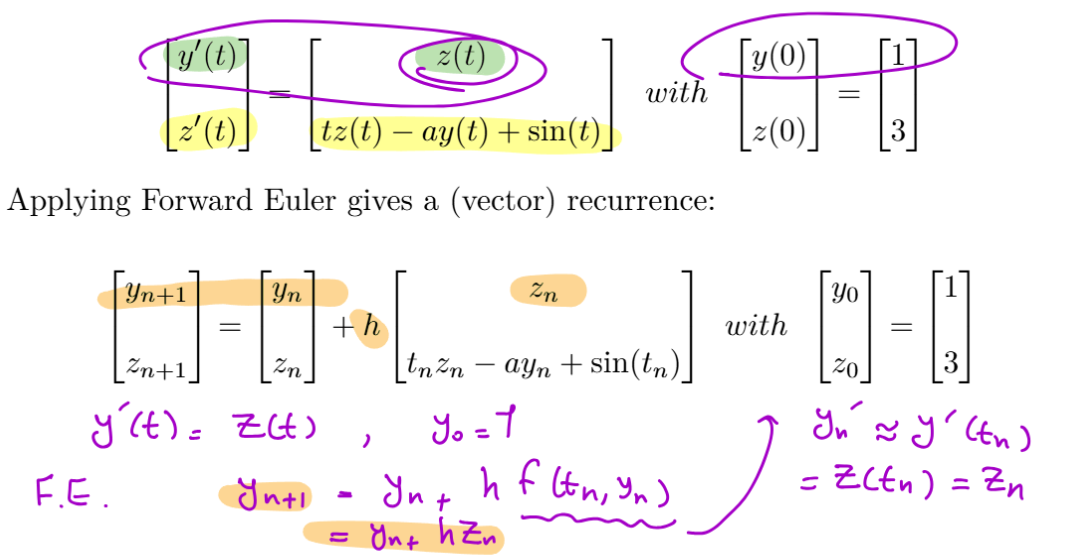

System of Equations

For systems of 1st order ODEs, we apply Forward Euler to each row in exactly the same way.

Error of Forward Euler Method

F.E. is $$y_{n+1} = y_n + hf(t_n, y_n)$$

Taylor series is:

The error for one step is the difference between these, assuming exact data at time

- i.e.

In this case, Forward Euler becomes:

The difference is:

This is the Local Truncation Error (LTE) of Forward Euler!

- As

decreases, LTE decreases quadratically

More accurate time-stepping

Keeping more terms in the series will help derive higher order schemes!

Trapezoidal Rule

Trapezoidal Scheme is:

The Local Truncation Error for trapezoidal rules is

Can we make it explicit?

Modified / Improved Euler

- Take forward Euler step to estimate the end point

- Evaluate slope there

- Use this approximate end-of-step slope in the trapezoidal formula

This looks like:

Explicit scheme with LTE

Backwards Euler Method

Implicit Scheme

- Similar to forward Euler

Its LTE is

Explicit “Runge Kutta” schemes

A family of explicit schemes (including improved Euler) written as:

4th Order Runge Kutta

LTE of

Similar schemes exist for higher orders,

Again, evaluate

Midpoint Method

Another explicit Runge Kutta scheme with LTE

Equivalent Expression

Local vs Global Error

The Global Error is the total error accumulated at the final time

- Global error is typically more important since our goal is to predict some final future value

For a constant step, computing from to end time

Then, for a given method we have:

i.e. one degree lower than LTE

Multi-step Schemes

One way to derive them is by fitting curves to current and earlier data points, for better slope estimates.

E.g. fit a quadratic to previous, current, and next step

Backward Differentiation Formulas Methods (BDF)

BDF1, BDF2, BDF3, etc.

- Number indicates order of global error

BDF1 = Backward Eular

Generalize the backwards Euler scheme

to higher order using earlier step info.

BDF2 uses current and previous step data:

BDF has LTE

General Form

The same approach extends to higher orders, yielding implicit schemes with the general form

With

Explicit Multistep Scheme

Adams-Bashforth

e.g. 2nd order:

LTE is

Higher Order ODEs

The order of the ODE is the highest derivative that appears

- e.g. an ODE with at most third derivates gives a 3rd order ODE

Converting to First Order

The general form for such a higher ODE looks like

We can convert them to systems of first order ODEs

- Change of variables

For each variablewith more than a first derivative, introduce new variables:

for

Substituting the new variables into the original ODE leads to:

- One first order equation for each original equation

- One or more additional equations relating the new variables

Stability of Time-Stepping Schemes

Since errors are generally

But, error/perturbations in initial conditions may lead to vastly different or incorrect answers.

If some initial error

Test Equation

We’ll consider a simple linear ODE, our “test equation”,

for constant

The exact solution is

- Tends to 0 as

Our Approach

- Apply a given time stepping scheme to our test equation

- Find the closed form of its numerical solution and error behaviour

- Find the conditions on the timestep

that ensure stability (error approaching zero)

Stability of Forward Euler

It is conditionally stable when

Stability of Backward/Implicit Euler

It is unconditionally stable

Large time steps still usually induce Large truncation error

Stability of Improved Euler

It is conditionally stable when

- Same as Forward Euler

Stability in general

For our linear test equation

For nonlinear problems, stability depends on

For systems of ODEs, stability relates to the eigenvalues of the “Jacobian” matrix

Truncation Error vs Stability

Stability tells us what our numerical algorithm itself does to small errors

Truncation error tells us how the accuracy of our numerical solution scales with time step

Determining LTE

- Replace approximations on RHS with exact versions

- Taylor expand all RHS quantities about time

- Taylor expand the exact solution

to compare against - Compute difference

. Lowest degree non-cancelling power of gives the LTE

Time Step Control

Trade-offs

Smaller

Larger

Minimize effort/cost by choosing largest

Adaptive Time-Stepping

Rate of change of the solution often varies over time!

- Adapt the time step during the computation to keep error small, while minimizing wasted effort

If we knew the error for a given

… but if we already knew the exact error, we’d also know the solution

Approach

Use two different time-stepping schemes together. Compare their results to estimate the error, and adjust

Adaptive Time-Stepping using Order

Idea:

- Run 2 methods simultaneously with different truncation error orders

- Approximate the error as

where has and has - If err > threshold, reduce

(halve it) and recompute the step again, until the threshold is satisfied - Estimate the error coefficient

as

where

plug in

Given a desired error tolerance

To (roughly) compensate for our approximations, we may be conservative by scaling