Numerical Linear Algebra

The study of algorithms for performing linear algebra operations numerically

- Matrix/vector arithmetic

- Solving linear systems of equations

- Taking norms

- Factoring & inverting systems of equations

- Finding eigenvalues/eigenvectors

Numerical methods often differ from familiar exact methods, due to: - efficiency concerns

- floating point error

- stability

- etc.

Page Rank

Idea: If many web pages link to your website, there must be a consensus that it is important

Web Links as a Graph

We represent the web’s structure as a directed graph

- Nodes (circles) represent pages

- Arcs (arrows) represent links from one page to another

We will use degree to refer to a node’s outdegree - the number of arcs leaving the node

Adjacency Matrix

Then the degree for node

Notice: Matrix

Interpreting Links as Votes

If page

- Outgoing links of a page

have equal influence, so the importance that gives to is: $$\frac{1}{deg(j)}$$

Global Importance

If page

- What if page

has just one incoming link, but the link is from page , and has many incoming links? - Then

is probably fairly important too!

- Then

The Random Surfer Model

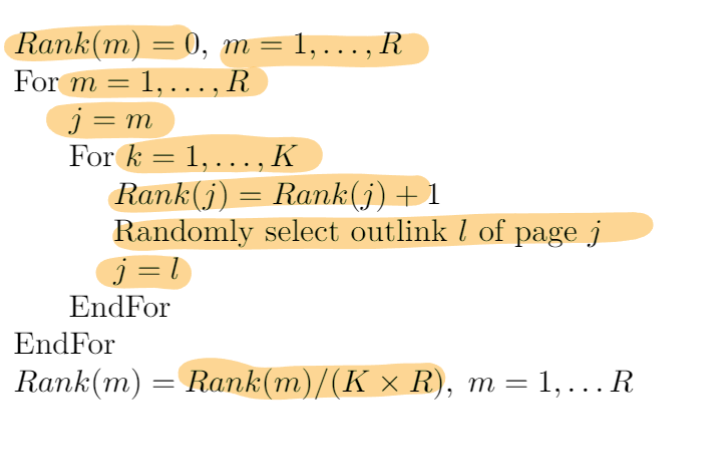

Imagine an internet user who starts at a page, and follows links at random from page to page for K steps

- They will probably end up on important pages more often

Then, select a new start page, and followrandom links again. Repeat the process times, starting from each page.

At the end, we estimate overall importance as:$$\text{Rank(page i) = (Visits to page i)/(Total visits to all pages) = (Visits to page i)/()}$$

Criticisms

Potential issues with this algorithm?

- The number of real web pages is monstrously huge

- ~1 billion unique hostnames

- many iterations needed

- Number of steps is taken per random surf sequence must be large, to get a representative sample

- What about dead end links?

- stuck on one page!

- What about cycles in the graph?

- Stuck on a closed subset of pages

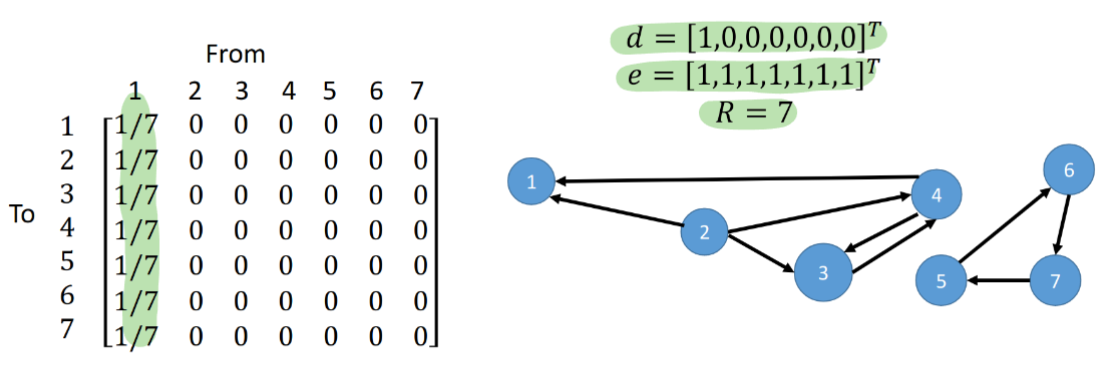

A Markov Chain Matrix

Let

We can build this matrix

- Divide all entries of each column of

by the column sum (out-degree of the node)

Dead Ends

To deal with dead-end links, we will simply teleport to a new page at random!

- if

is the number of pages, we augment to get defined by:$$P' = P+\frac{1}{R}ed^T$$ - The matrix

is a matrix of probabilities such that from any dead end page , we transition to every other page with equal probability

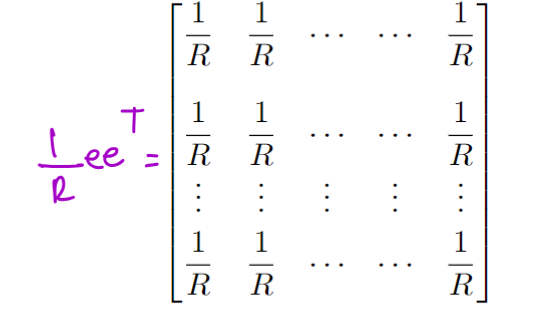

Escaping Cycles

Most of the time (a fraction

- Occasionally wish some probability,

, teleport from any page to any other page with equal probability, regardless of links$$M=\alpha P'+(1-\alpha)\frac{1}{R}ee^T$$ - The

matrix looks like:

We will call the combined matrixour Google matrix - Most of the time this just follows links

- and always teleports out of dead ends

- Also occasionally teleports randomly to escape cycles

Google purportedly used

The sum of each column is 1

Some Useful Properties of

The entries of

Each column of

Interpretation: If we are on a webpage, probability of being on some webpage after a transition is 1

- we can’t just disappear

Markov Transition Matrices

The Google Matrix

We define a Markov matrix

Probability Vector

Now, define a probability vector as a vector

If the surfer starts at a random page with equal probabilities, this can be represented by a probability vector, where

- If a surfer starts at a specific page, that entry will have probability 1 and others will have probability 0

Evolving the Probability Vector

Now we have:

- the probability vector describing the initial state,

- a Markov matrix

describing the transition probabilities among pages

Their producttells us the probabilities of our surfer being at each page after one transition

Preserving a Probability Vector

If

- Yes!

Page Rank Idea

With what probability does our surfer end up at each page after many steps, starting from

- i.e. What is

? - higher probability in

implies greater importance - then we can rank the pages by this importance measure

Questions:

- then we can rank the pages by this importance measure

- Do we actually know if it will settle/converge to a fixed final result

- If yes, then how long will it take? Roughly how many iterations are needed before we can stop?

- Can we implement this efficiently?

Making Page Rank Efficient

How can we apply/implement Page Rank in a way that is computationally feasible?

- We’ll exploit precomputation and sparsity

Precomputation

The ranking vector

- to later search for a keyword, Google finds only the subset of pages matching the keywords, and ranks those by their precomputed values in

Sparsity

In numerical linear algebra, we often deal with two kinds of matrices

- Dense: Most or all entries are non-zero. Store in an

array, manipulate “normally” - Sparse: Most entries are zero. Use a “sparse” data structure to save space and time

- prefer algorithms that avoid “destroying” sparsity

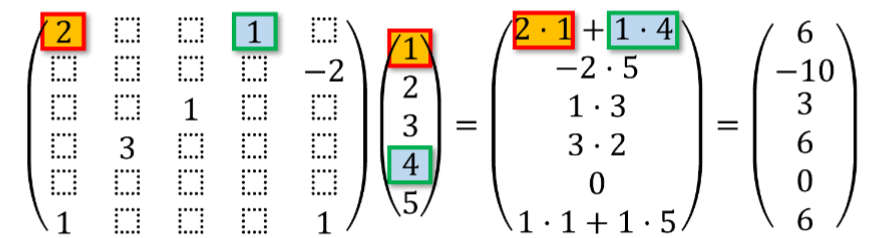

Sparse Matrix-Vector Multiplication

Multiplying a sparse matrix with a vector can be done efficiently

- Only non-zero matrix entries are ever accessed/used

Exploiting Sparsity

Note:

The trick: Use linear algebra manipulations to perform the main iteration$$p^{n+1}=Mp^n$$without ever creating/storing

Recall:

Consider computing:

We never form

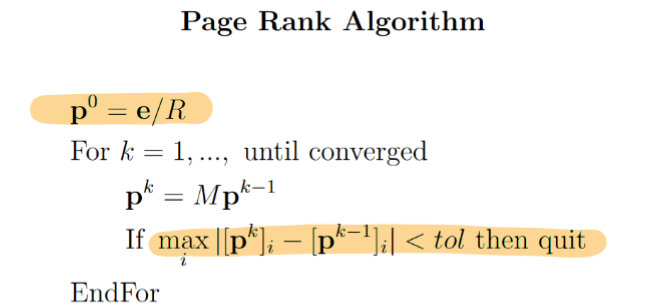

Given this efficient/sparse iteration, loop until the max change in probability vector per step is small (< tol)

Google Search: Other Factors

Page Rank can be “tweaked” to incorporate other (commercial?) factors.

Replace standard teleportation

- In modern search engines, many factors beside pure link-based ranking can come into play

Convergence of Page Rank

We will need some additional facts about Markov Matrices, involving eigenvalues and eigenvectors

Eigenvalues and Eigenvectors

An eigenvalue

Equivalently, this can be written as$$Qx=\lambda I x$$where

Rearranging gives$$(\lambda I - Q)x = 0$$which implies that the matrix

Singular

A singular matrix

Thus to find the eigenvalues

plug

Properties

det(A − λI) = 0 → eigenvalues

- tr(A) = sum of eigenvalues

- det(A) = product of eigenvalues

- A invertible ⇔ 0 not an eigenvalue

- A diagonalizable ⇔ n lin. indep. eigenvectors

- Symmetric ⇒ diagonalizable w/ real eigenvalues

- Triangular ⇒ eigenvalues = diagonal entries

Convergence Properties

- Every Markov matrix

has 1 as an eigenvalue - Every eigenvalue of a Markov matrix Q satisfies

- So 1 is the largest eigenvalue

- A Markov matrix

is a positive Markov matrix if - If

is a positive Markov matrix, then there is only one linearly independent eigenvector of with

The number of iterations required for Page Rank to converge to the final vectordepends on the size of the 2nd largest eigenvalue,

- Then 2nd largest eigenvalue dictates the slowest rate at which the unwanted component of

are shrinking

Result

For google matrix,

- where

dictated the balance between following real links, and teleporting randomly

After 114 iterations, any vector components of

- The resulting vector

is likely to be a good approximation of the dominant eigenvector,

A smaller value of

- Should we speed it up by choosing a small

?

NO!implies only random teleportation. trades off accuracy for efficiency

Gaussian Elimination

Solving Linear Systems of Equations

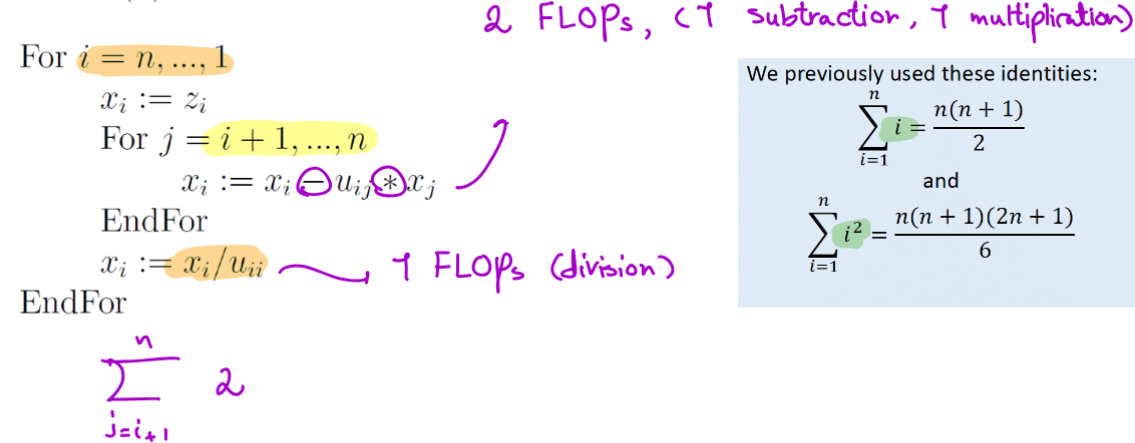

Cost of Triangular Solve

Triangular solves cost

Factorization cost dominates when

- Given an existing factorization, solving for new RHS’s is cheap:

Row Subtraction via Matrices

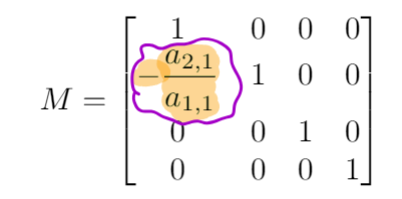

Zeroing a (sub-diagonal) entry of a column by row subtraction can be written as applying a specific matrix

where

is the original matrix is the matrix after subtracting the specific row

can be written as a matrix:

is the identity matrix, but with a zero entry replaced by the (negative of the) necessary multiplicative factor

So, the whole process of factorization can be viewed as a sequence of matrix (left-)multiplications applied to- The matrix left at the end is

Therefore:

- Define

and we have our factorization!

Interleaving the permutation matricesbefore each similarly leads to the factorization

Inverse of

What is

- The inverse of the simple matrix form is the same matrix, but with the off–diagonal entry negated

Costs: Solving

An obvious alternative for solving

- Inver

to get - Multiply

to get

One can show that the above is actually more expensive than using our factor and triangular solve strategy

- It also generally incurs more floating point error

- Most numerical algorithms avoid ever computing

Norms and Conditioning

Norms are measurements of “size”/magnitude for vectors or matrices

Conditioning describes how the output of a function/operation/matrix changes due to changes in input

Vector Norms

There are many reasonable norms for a vector,

Common choices are:

- 1-norm (or taxicab/Manhattan norm):

- 2-norm (or Euclidean norm):

-norm (or max norm):

These are collectively called

- Only holds in the limit for

case

Key Properties of Norms

If the norm is zero, then the vector must be the zero-vector

The norm of a scaled vector must satisfy

The triangle inequality holds:

Defining Norms for Matrices

Matrix norms are often defined/”induced” as follows, using

- Clearly we can’t try out all possible

to determine this - There are simpler equivalent definitions in some cases:

- Max absolute column sum

* Max absolute row sum

Matrix 2-norm

Using the vector 2-norm, we get the matrix 2-norm, or spectral norm:

The matrix’s 2-norm relates to the eigenvalues

Specifically, if

Matrix Norm Properties

for all scalar

Conditioning of Linear Systems

Conditioning describes how the output of a function/operation/problem changes due to changes in input

- Conditioning is indicative of how difficult a problem is to solve, independent of the algorithm/numerical method used

- Norms are useful in understanding linear system conditioning

For a linear system

- How much does a perturbation of

cause the solution to change? - How much does a perturbation of

cause the solution to change?

For a given perturbation, we say the system is:

- Well-conditioned if

changes little - Ill-conditioned if

changes lots

For an ill-conditioned system, small errors can be radically magnified!

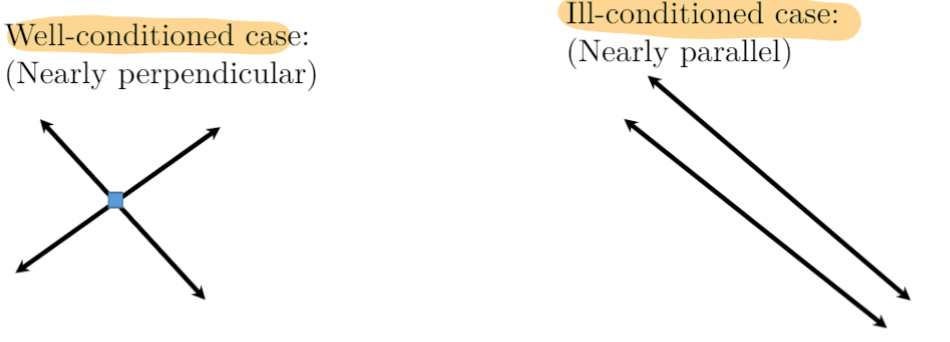

Geometric Intuition: Line Intersection

Well-conditioned case: Nearly perpendicular lines

Ill-conditioned case: Nearly parallel lines

Condition Number Summary

Condition number of a matrix

is well-conditioned is ill-conditioned

For systemprovides upper bounds on relative change in due to relative change in

or in

We defined the condition number as

without specifying which norm. Different norms will give different

We can specify the norm with a subscript, e.g., $$\kappa(A)_2=|A|_2\cdot|A^{-1}|_2$$

If unspecified, always assume the 2-norm

Equivalence of Norms

The norms we’ve looked at differ from one another by no more than a constant factor

That is$$C_1|x|_a\leq |x|b\leq C_2|x|_a$$

for constants

Numerical Solutions: Residuals and Errors

Condition number plays a role in understanding/bounding the accuracy of numerical solutions

If we compute an approximate solution

- we need the exact solution

for comparison - recall: relative error =

Residual

As a proxy for error, we often use the residual

i.e., by how much does out computed solution fail to satisfy the original problem?

- This we can compute easily!

- We know

our computed

Residual vs Errors

Assuming

So, applying our earlier bound using

Interpreting this Bound

The solution’s relative error,

Moral: If we (roughly) know

- if

, a small residual indicates a small relative error - But, if

is large, residual could still be small while error is quite large! - Again, this is independent of the algorithm used to compute

- Again, this is independent of the algorithm used to compute

Use of the Residual - Iterative Methods

Many alternate algorithms for solving

- Similar to PageRank, they iteratively improve a solution estimate

- Size of residual dictates when to stop

Gaussian Elimination & Error

In floating point, Gaussian elimination with pivoting on

- GE’s numerical result

gives the exact solution to a nearby problem (i.e. with perturbed )

where

Again, applying our earlier bound gives

e.g. if

Conditioning is algorithm-independent

Condition is a property of the problem itself

- not a property of a particular algorithm

- i.e., A system

is well- or ill-conditioned, independent of how we choose to solve it

Even an “ideal” numerical algorithm can’t guarantee a solution will small error if